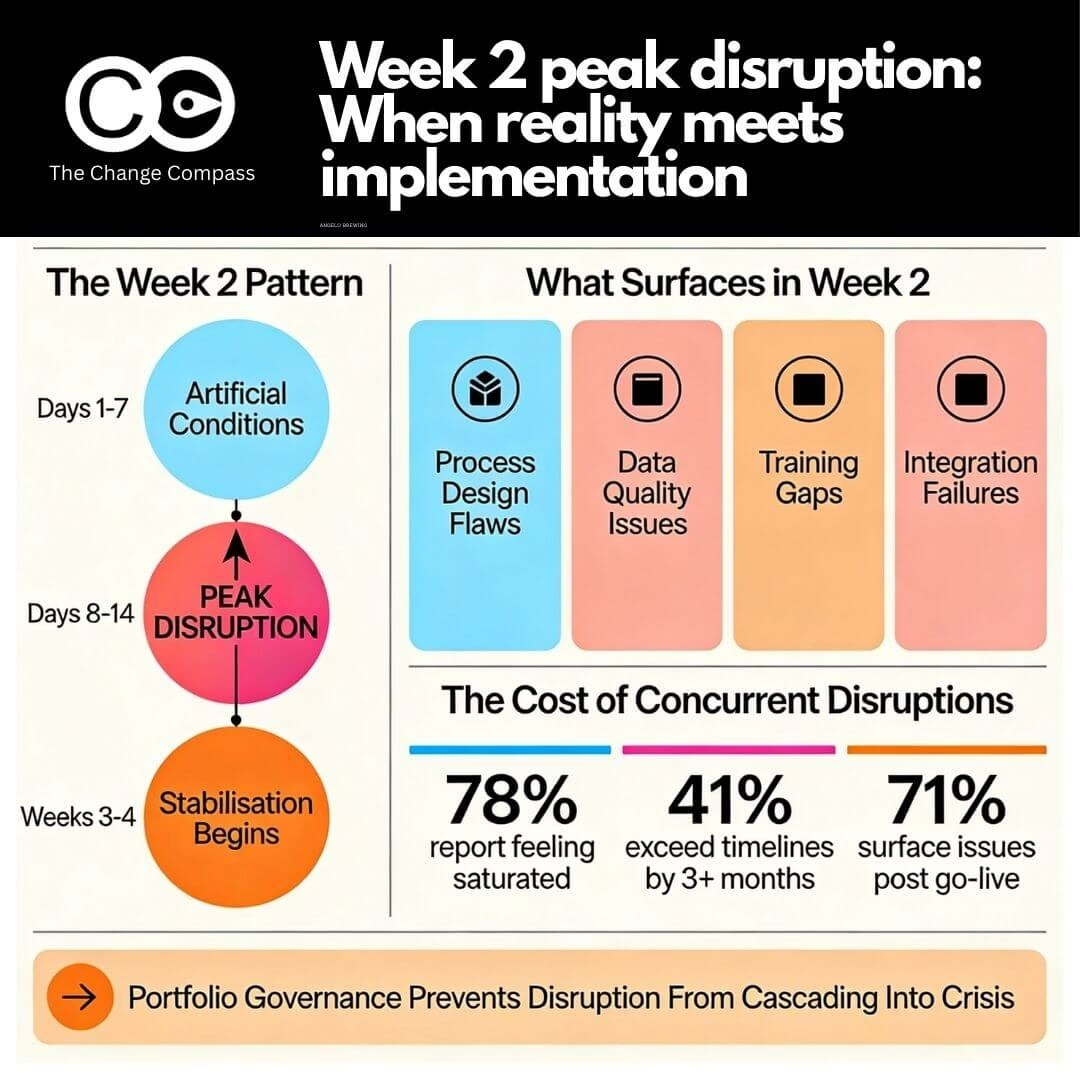

Most organisations anticipate disruption around go-live. That’s when attention focuses on system stability, support readiness, and whether the new process flows will actually work. But the real crisis arrives 10 to 14 days later.

Week two is when peak disruption hits. Not because the system fails, as often it’s running adequately by then, but because the gap between how work was supposed to work and how it actually works becomes unavoidable. Training scenarios don’t match real workflows. Data quality issues surface when people need specific information for decisions. Edge cases that weren’t contemplated during design hit customer-facing teams. Workarounds that started as temporary solutions begin cascading into dependencies.

This pattern appears consistently across implementation types. EHR systems experience it. ERP platforms encounter it. Business process transformations face it. The specifics vary, but the timing holds: disruption intensity peaks in week two, then either stabilises or escalates depending on how organisations respond.

Understanding why this happens, what value it holds, and how to navigate it strategically is critical, especially when organisations are managing multiple disruptions simultaneously across concurrent projects. That’s where most organisations genuinely struggle.

The pattern: why disruption peaks in week 2

Go-live day itself is deceptive. The environment is artificial. Implementation teams are hypervigilant. Support staff are focused exclusively on the new system. Users know they’re being watched. Everything runs at artificial efficiency levels.

By day four or five, reality emerges. Users relax slightly. They try the workflows they actually do, not the workflows they trained on. They hit the branch of the process tree that the scripts didn’t cover. A customer calls with a request that doesn’t fit the designed workflow. Someone realises they need information from the system that isn’t available in the standard reports. A batch process fails because it references data fields that weren’t migrated correctly.

These issues arrive individually, then multiply.

Research on implementation outcomes shows this pattern explicitly. A telecommunications case study deploying a billing system shows week one system availability at 96.3%, week two still at similar levels, but by week two incident volume peaks at 847 tickets per week. Week two is not when availability drops. It’s when people discover the problems creating the incidents.

Here’s the cascade that makes week two critical:

Days 1 to 7: Users work the happy paths. Trainers are embedded in operations. Ad-hoc support is available. Issues get resolved in real time before they compound. The system appears to work.

Days 8 to 14: Implementation teams scale back support. Users begin working full transaction volumes. Edge cases emerge systematically. Support systems become overwhelmed. Individual workarounds begin interconnecting. Resistance crystallises, and Prosci research shows resistance peaks 2 to 4 weeks post-implementation. By day 14, leadership anxiety reaches a peak. Finance teams close month-end activities and hit system constraints. Operations teams process their full transaction volumes and discover performance issues. Customer service teams encounter customer scenarios not represented in training.

Weeks 3 to 4: Either stabilisation occurs through focused remediation and support intensity, or problems compound further. Organisations that maintain intensive support through week two recover within 60 to 90 days. Those that scale back support too early experience extended disruption lasting months.

The research quantifies this. Performance dips during implementation average 10 to 25%, with complex systems experiencing dips of 40% or more. These dips are concentrated in weeks 1 to 4, with week two as the inflection point. Supply chain systems average 12% productivity loss. EHR systems experience 5 to 60% depending on customisation levels. Digital transformations typically see 10 to 15% productivity dips.

The depth of the dip depends on how well organisations manage the transition. Without structured change management, productivity at week three sits at 65 to 75% of pre-implementation levels, with recovery timelines extending 4 to 6 months. With effective change management and continuous support, recovery happens within 60 to 90 days.

Understanding the value hidden in disruption

Most organisations treat week-two disruption as a problem to minimise. They try to manage through it with extended support, workarounds, and hope. But disruption, properly decoded, provides invaluable intelligence.

Each issue surfaced in week two is diagnostic data. It tells you something real about either the system design, the implementation approach, data quality, process alignment, or user readiness. Organisations that treat these issues as signals rather than failures extract strategic value.

Process design flaws surface quickly.

A customer-service workflow that seemed logical in design fails when customer requests deviate from the happy path. A financial close process that was sequenced one way offline creates bottlenecks when executed at system speed. A supply chain workflow that assumed perfect data discovers that supplier codes haven’t been standardised. These aren’t implementation failures. They’re opportunities to redesign processes based on actual operational reality rather than theoretical process maps.

Integration failures reveal incompleteness.

A data synchronisation issue between billing and provisioning systems appears in week two when the volume of transactions exposing the timing window is processed. A report that aggregates data from multiple systems fails because one integration wasn’t tested with production data volumes. An automated workflow that depends on customer master data being synchronised from an upstream system doesn’t trigger because the synchronisation timing was wrong. These issues force the organisation to address integration robustness rather than surfacing in month six when it’s exponentially more costly to fix.

Training gaps become obvious.

Not because users lack knowledge, as training was probably thorough, but because knowledge retention drops dramatically once users are under operational pressure. That field on a transaction screen no one understood in training becomes critical when a customer scenario requires it. The business rule that sounded straightforward in the classroom reveals nuance when applied to real transactions. Workarounds start emerging not because the system is broken but because users revert to familiar mental models when stressed.

Data quality problems declare themselves.

Historical data migration always includes cleansing steps. Week two is when cleansed data collides with operational reality. Customer address data that was “cleaned” still has variants that cause matching failures. Supplier master data that was de-duplicated still includes records no one was aware of. Inventory counts that were migrated don’t reconcile with physical systems because the timing window wasn’t perfect. These aren’t test failures. They’re production failures that reveal where data governance wasn’t rigorous enough.

System performance constraints appear under load.

Testing runs transactions in controlled batches. Real operations involve concurrent transaction volumes, peak period spikes, and unexpected load patterns. Performance issues that tests didn’t surface appear when multiple users query reports simultaneously or when a batch process runs whilst transaction processing is also occurring. These constraints force decisions about infrastructure, system tuning, or workflow redesign based on evidence rather than assumptions.

Adoption resistance crystallises into actionable intelligence.

Resistance in weeks 1 to 2 often appears as hesitation, workaround exploration, or question-asking. By week two, if resistance is adaptive and rooted in legitimate design or readiness concerns, it becomes specific. “The workflow doesn’t work this way because of X” is more actionable than “I’m not ready for this system.” Organisations that listen to week-two resistance can often redesign elements that actually improve the solution.

The organisations that succeed at implementation are those that treat week-two disruption as discovery rather than disaster. They maintain support intensity specifically because they know disruption reveals critical issues. They establish rapid response mechanisms. They use the disruption window to test fixes and process redesigns with real operational complexity visible for the first time.

This doesn’t mean chaos is acceptable. It means disruption, properly managed, delivers value.

The reality when disruption stacks: multiple concurrent go-lives

The week-two disruption pattern assumes focus. One system. One go-live. One disruption window. Implementation teams concentrated. Support resources dedicated. Executive attention singular.

This describes almost no large organisations actually operating today.

Most organisations manage multiple implementations simultaneously. A financial services firm launches a new customer data platform, updates its payments system, and implements a revised underwriting workflow across the same support organisations and user populations. A healthcare system deploys a new scheduling system, upgrades its clinical documentation platform, and migrates financial systems, often on overlapping timelines. A telecommunications company implements BSS (business support systems) whilst updating OSS (operational support systems) and launching a new customer portal.

When concurrent disruptions overlap, the impacts compound exponentially rather than additively.

Disruption occurring at week two for Initiative A coincides with go-live week one for Initiative B and the first post-implementation month for Initiative C. Support organisations are stretched across three separate incident response mechanisms. Training resources are exhausted from Initiative A training when Initiative B training ramps. User psychological capacity, already strained from one system transition, absorbs another concurrently.

Research on concurrent change shows this empirically. Organisations managing multiple concurrent initiatives report 78% of employees feeling saturated by change. Change-fatigued employees show 54% higher turnover intentions compared to 26% for low-fatigue employees. Productivity losses don’t add up; they cascade. One project’s 12% productivity loss combined with another’s 15% loss doesn’t equal 27% loss. Concurrent pressures often drive losses exceeding 40 to 50%.

The week-two peak disruption of Initiative A, colliding with go-live intensity for Initiative B, creates what one research study termed “stabilisation hell”, a period where organisations struggle simultaneously to resolve unforeseen problems, stabilise new systems, embed users, and maintain business-as-usual operations.

Consider a real scenario. A financial services firm deployed three major technology changes into the same operations team within 12 weeks. Initiative A: New customer data platform. Initiative B: Revised loan underwriting workflow. Initiative C: Updated operational dashboard.

Week four saw Initiative A hit its week-two peak disruption window. Incident volumes spiked. Data quality issues surfaced. Workarounds proliferated. Support tickets exceeded capacity. Week five, Initiative B went live. Training for a new workflow began whilst Initiative A fires were still burning. Operations teams were learning both systems on the fly.

Week eight, Initiative C launched. By then, operations teams had learned two new systems, embedded neither, and were still managing Initiative A stabilisation issues. User morale was low. Stress was high. Error rates were increasing. The organisation had deployed three initiatives but achieved adoption of none. Each system remained partially embedded, each adoption incomplete, each system contributing to rather than resolving operational complexity.

Research on this scenario is sobering. 41% of projects exceed original timelines by 3+ months. 71% of projects surface issues post go-live requiring remediation. When three projects encounter week-two disruptions simultaneously or overlappingly, the probability that all three stabilise successfully drops dramatically. Adoption rates for concurrent initiatives average 60 to 75%, compared to 85 to 95% for single initiatives. Recovery timelines extend from 60 to 90 days to 6 to 12 months or longer.

The core problem: disruption is valuable for diagnosis, but only if organisations have capacity to absorb it. When capacity is already consumed, disruption becomes chaos.

Strategies to prevent operational collapse across the portfolio

Preventing operational disruption when managing concurrent initiatives requires moving beyond project-level thinking to portfolio-level orchestration. This means designing disruption strategically rather than hoping to manage through it.

Step 1: Sequence initiatives to prevent concurrent peak disruptions

The most direct strategy is to avoid allowing week-two peak disruptions to occur simultaneously.

This requires mapping each initiative’s disruption curve. Initiative A will experience peak disruption weeks 2 to 4. Initiative B, scheduled to go live once Initiative A stabilises, will experience peak disruption weeks 8 to 10. Initiative C, sequenced after Initiative B stabilises, disrupts weeks 14 to 16. Across six months, the portfolio experiences three separate four-week disruption windows rather than three concurrent disruption periods.

Does sequencing extend overall timeline? Technically yes. Initiative A starts week one, Initiative B starts week six, Initiative C starts week twelve. Total programme duration: 20 weeks vs 12 weeks if all ran concurrently. But the sequencing isn’t linear slowdown. It’s intelligent pacing.

More critically: what matters isn’t total timeline, it’s adoption and stabilisation. An organisation that deploys three initiatives serially over six months with each fully adopted, stabilised, and delivering value exceeds in value an organisation that deploys three initiatives concurrently in four months with none achieving adoption above 70%.

Sequencing requires change governance to make explicit trade-off decisions. Do we prioritise getting all three initiatives out quickly, or prioritise adoption quality? Change portfolio management creates the visibility required for these decisions, showing that concurrent Initiative A and B deployment creates unsustainable support load, whereas sequencing reduces peak support load by 40%.

Step 2: Consolidate support infrastructure across initiatives

When disruptions must overlap, consolidating support creates capacity that parallel support structures don’t.

Most organisations establish separate support structures for each initiative. Initiative A has its escalation path. Initiative B has its own. Initiative C has its own. This creates three separate 24-hour support rotations, three separate incident categorisation systems, three separate communication channels.

Consolidated support establishes one enterprise support desk handling all issues concurrently. Issues get triaged to the appropriate technical team, but user-facing experience is unified. A customer-service representative doesn’t know whether their problem stems from Initiative A, B, or C, and shouldn’t have to. They have one support number.

Consolidated support also reveals patterns individual support teams miss. When issues across Initiative A and B appear correlated, when Initiative B’s workflow failures coincide with Initiative A data synchronisation issues, consolidated support identifies the dependency. Individual teams miss this connection because they’re focused only on their initiative.

Step 3: Integrate change readiness across initiatives

Standard practice means each initiative runs its own readiness assessment, designs its own training programme, establishes its own change management approach.

This creates training fragmentation. Users receive five separate training programmes from five separate change teams using five different approaches. Training fatigue emerges. Messaging conflicts create confusion.

Integrated readiness means:

- One readiness framework applied consistently across all initiatives

- Consolidated training covering all initiatives sequentially or in integrated learning paths where possible

- Unified change messaging that explains how the portfolio of changes supports a coherent organisational direction

- Shared adoption monitoring where one dashboard shows readiness and adoption across all initiatives simultaneously

This doesn’t require initiatives to be combined technically. Initiative A and B remain distinct. But from a change management perspective, they’re orchestrated.

Research shows this approach increases adoption rates 25 to 35% compared to parallel change approaches.

Step 4: Create structured governance over portfolio disruption

Change portfolio management governance operates at two levels:

Initiative level: Sponsor, project manager, change lead, communications lead manage Initiative A’s execution, escalations, and day-to-day decisions.

Portfolio level: Representatives from all initiatives meet fortnightly to discuss:

- Emerging disruptions across all initiatives

- Support load analysis, identifying where capacity limits are being hit

- Escalation patterns and whether issues are compounding across initiatives

- Readiness progression and whether adoption targets are being met

- Adjustment decisions, including whether to slow Initiative B to support Initiative A stabilisation

Portfolio governance transforms reactive problem management into proactive orchestration. Instead of discovering in week eight that support capacity is exhausted, portfolio governance identifies the constraint in week four and adjusts Initiative B timeline accordingly.

Tools like The Change Compass provide the data governance requires. Real-time dashboards show support load across initiatives. Heatmaps reveal where particular teams are saturated. Adoption metrics show which initiatives are ahead and which are lagging. Incident patterns identify whether issues are initiative-specific or portfolio-level.

Step 5: Use disruption windows strategically for continuous improvement

Week-two disruptions, whilst painful, provide a bounded window for testing process improvements. Once issues surface, organisations can test fixes with real operational data visible.

Rather than trying to suppress disruption, portfolio management creates space to work within it:

Days 1 to 7: Support intensity is maximum. Issues are resolved in real time. Limited time for fundamental redesign.

Days 8 to 14: Peak disruption is more visible. Teams understand patterns. Workarounds have emerged. This is the window to redesign: “The workflow doesn’t work because X. Let’s redesign process Y to address this.” Changes tested at this point, with full production visibility, are often more effective than changes designed offline.

Weeks 3 to 4: Stabilisation period. Most issues are resolved. Remaining issues are refined through iteration.

Organisations that allocate capacity specifically for week-two continuous improvement often emerge with more robust solutions than those that simply try to push through disruption unchanged.

Operational safeguards: systems to prevent disruption from becoming crisis

Beyond sequencing and governance, several operational systems prevent disruption from cascading into crisis:

Load monitoring and reporting

Before initiatives launch, establish baseline metrics:

- Support ticket volume (typical week has X tickets)

- Incident resolution time (typical issue resolves in Y hours)

- User productivity metrics (baseline is Z transactions per shift)

- System availability metrics (target is 99.5% uptime)

During disruption weeks, track these metrics daily. When tickets approach 150% of baseline, escalate. When resolution times extend beyond 2x normal, adjust support allocation. When productivity dips exceed 30%, trigger contingency actions.

This monitoring isn’t about stopping disruption. It’s about preventing disruption from becoming uncontrolled. The organisation knows the load is elevated, has data quantifying it, and can make decisions from evidence rather than impression.

Readiness assessment across the portfolio

Don’t run separate readiness assessments. Run one portfolio-level readiness assessment asking:

- Which populations are ready for Initiative A?

- Which are ready for Initiative B?

- Which face concurrent learning demand?

- Where do we have capacity for intensive support?

- Where should we reduce complexity or defer some initiatives?

This single assessment reveals trade-offs. “Operations is ready for Initiative A but faces capacity constraints with Initiative B concurrent. Options: Defer Initiative B two weeks, assign additional change support resources, or simplify Initiative B scope for operations teams.”

Blackout periods and pacing restrictions

Most organisations establish blackout periods for financial year-end, holiday periods, or peak operational seasons. Many don’t integrate these with initiative timing.

Portfolio management makes these explicit:

- October to December: Reduced change deployment (year-end focus)

- January weeks 1 to 2: No major launches (people returning from holidays)

- July to August: Minimal training (summer schedules)

- March to April: Capacity exists; good deployment window

Planning initiatives around blackout periods and organisational capacity rhythms rather than project schedules dramatically improves outcomes.

Contingency support structures

For initiatives launching during moderate-risk windows, establish contingency support plans:

- If adoption lags 15% behind target by week two, what additional support deploys?

- If critical incidents spike 100% above baseline, what escalation activates?

- If user resistance crystallises into specific process redesign needs, what redesign process engages?

- If stabilisation targets aren’t met by week four, what options exist?

This isn’t pessimism. It’s realistic acknowledgement that week-two disruption is predictable and preparations can address it.

Integrating disruption management into change portfolio operations

Preventing operational disruption collapse requires integrating disruption management into standard portfolio operations:

Month 1: Portfolio visibility

- Map all concurrent initiatives

- Identify natural disruption windows

- Assess portfolio support capacity

Month 2: Sequencing decisions

- Determine which initiatives must sequence vs which can overlap

- Identify where support consolidation is possible

- Establish integrated readiness framework

Month 3: Governance establishment

- Launch portfolio governance forum

- Establish disruption monitoring dashboards

- Create escalation protocols

Months 4 to 12: Operational execution

- Monitor disruption curves as predicted

- Activate contingencies if necessary

- Capture continuous improvement opportunities

- Track adoption across portfolio

Tools supporting this integration, such as change portfolio platforms like The Change Compass, provide the visibility and monitoring capacity required. Real-time dashboards show disruption patterns as they emerge. Adoption tracking reveals whether initiatives are stabilising or deteriorating. Support load analytics identify bottleneck periods before they become crises.

For more on managing portfolio-level change saturation, see Managing Change Saturation: How to Prevent Initiative Fatigue and Portfolio Failure.

The research imperative: what we know about disruption

The evidence on implementation disruption is clear:

- Week-two peak disruption is predictable, not random

- Disruption provides diagnostic value when organisations have capacity to absorb and learn from it

- Concurrent disruptions compound exponentially, not additively

- Sequencing initiatives strategically improves adoption and stabilisation vs concurrent deployment

- Organisations with portfolio-level governance achieve 25 to 35% higher adoption rates

- Recovery timelines for managed disruption: 60 to 90 days; unmanaged disruption: 6 to 12 months

The alternative to strategic disruption management is reactive crisis management. Most organisations experience week-two disruption reactively, scrambling to support, escalating tickets, hoping for stabilisation. Some organisations, especially those managing portfolios, are choosing instead to anticipate disruption, sequence it thoughtfully, resource it adequately, and extract value from it.

The difference in outcomes is measurable: adoption, timeline, support cost, employee experience, and long-term system value.

Frequently asked questions

Why does disruption peak specifically at week 2, not week 1 or week 3?

Week one operates under artificial conditions: hypervigilant support, implementation team presence, trainers embedded, users following scripts. Real patterns emerge when artificial conditions end. Week two is when users attempt actual workflows, edge cases surface, and accumulated minor issues combine. Peak incident volume and resistance intensity typically occur weeks 2 to 4, with week two as the inflection point.

Should organisations try to suppress week-two disruption?

No. Disruption reveals critical information about process design, integration completeness, data quality, and user readiness. Suppressing it masks problems. The better approach: acknowledge disruption will occur, resource support intensity specifically for the week-two window, and use the disruption as diagnostic opportunity.

How do we prevent week-two disruptions from stacking when managing multiple concurrent initiatives?

Sequence initiatives to avoid concurrent peak disruption windows. Consolidate support infrastructure across initiatives. Integrate change readiness across initiatives rather than running parallel change efforts. Establish portfolio governance making explicit sequencing decisions. Use change portfolio tools providing real-time visibility into support load and adoption across all initiatives.

What’s the difference between well-managed disruption and unmanaged disruption in recovery timelines?

Well-managed disruption with adequate support resources, portfolio orchestration, and continuous improvement capacity returns to baseline productivity within 60 to 90 days post-go-live. Unmanaged disruption with reactive crisis response, inadequate support, and no portfolio coordination extends recovery timelines to 6 to 12 months or longer, often with incomplete adoption.

Can change portfolio management eliminate week-two disruption?

No, and that’s not the goal. Disruption is inherent in significant change. Portfolio management’s purpose is to prevent disruption from cascading into crisis, to ensure organisations have capacity to absorb disruption, and to extract value from disruption rather than merely enduring it.

How does the size of an organisation affect week-two disruption patterns?

Patterns appear consistent: small organisations, large enterprises, government agencies all experience week-two peak disruption. Scale affects the magnitude. A 50-person firm’s week-two disruption affects everyone directly, whilst a 5,000-person firm’s disruption affects specific departments. The timing and diagnostic value remain consistent.

What metrics should we track during the week-two disruption window?

Track system availability (target: maintain 95%+), incident volume (expect 200%+ of normal), mean time to resolution (expect 2x baseline), support ticket backlog (track growth and aging), user productivity in key processes (expect 65 to 75% of baseline), adoption of new workflows (expect initial adoption with workaround development), and employee sentiment (expect stress with specific resistance themes).

How can we use week-two disruption data to improve future implementations?

Document incident patterns, categorise by root cause (design, integration, data, training, performance), and use these insights for process redesign. Test fixes during week-two disruption when full production complexity is visible. Capture workarounds users develop, as they often reveal legitimate unmet needs. Track which readiness interventions were most effective. Use this data to tailor future implementations.