The way you lead change at scale reveals everything about your organisation’s real capabilities. It exposes leadership gaps you didn’t know existed, illuminates cultural assumptions that have been invisible, and forces you to confront the hard truth about whether your people actually have capacity to transform. Most organisations aren’t prepared for what that mirror shows them.

But here’s what the research tells us: organisations that navigate this successfully share a specific set of practices – and they’re not what you’d expect from traditional change management playbooks.

The data imperative: Why gut feel doesn’t scale

Let’s start with a hard truth.

Leading change at scale without data is leadership theatre, not leadership.

When you’re managing a single, relatively contained change initiative, you might get away with staying close to the action, holding regular conversations with leaders, and making decisions based on what people tell you. But once you cross into transformation territory – where multiple initiatives run concurrently, impact ripples across departments, and competing priorities fragment focus – relying on conversation alone becomes a liability.

Large‑scale reviews of change and implementation outcomes show that organisations with robust, continuous feedback loops and structured measurement achieve significantly higher adoption and effectiveness than those relying on infrequent or informal feedback alone. The problem isn’t what people say in meetings. It’s that without data context, you’re only hearing from the loudest voices, the most available people, and those comfortable speaking up.

Consider a real scenario: a large financial services firm launched three major initiatives simultaneously. Line leaders reported strong engagement. Senior leaders felt confident about adoption trajectories. Yet underlying data revealed a very different picture – store managers were involved in seven out of eight change initiatives across the portfolio, with competing time demands creating unrealistic workload conditions. This saturation was driving resistance, but because no one was measuring change portfolio impact holistically, the signal was invisible until adoption rates collapsed three months post-go-live.

Data-driven change leadership serves a critical function: it provides the whole-system visibility that conversations alone cannot deliver. It enables leaders to move beyond intuition and opinion to evidence-based decisions about resourcing, timing, and change intensity.

What this means practically:

- Establish clear metrics before change launches. Don’t wait until mid-implementation to decide what you’re measuring. Define adoption targets, readiness baselines, engagement thresholds, and business impact indicators upfront. This removes bias from after-the-fact analysis.

- Use continuous feedback loops, not annual reviews. Research shows organisations using continuous measurement achieve 25-35% higher adoption rates than those conducting single-point assessments. Monthly or quarterly pulse checks on readiness, adoption, and engagement allow you to identify emerging issues and adjust course in real time.

- Democratise change data across your leadership team. When only change professionals have visibility into change metrics, leaders lack the context to make informed decisions. Share adoption dashboards, readiness scores, and sentiment data with line leaders and executives. Help them understand what the data means and where to intervene.

- Test hypotheses, don’t rely on assumptions. Before committing resources to particular change strategies or interventions, form testable hypotheses. For example: “We hypothesise that readiness is low in Department A because of communication gaps, not capability gaps.” Then design minimal data collection to confirm or reject that hypothesis. This moves you from reactive problem-solving to strategic targeting.

The shift from gut-feel to data-driven change is neither simple nor quick, but the business case is overwhelming. Organisations with robust feedback loops embedded throughout transformation are 6.5 times more likely to experience effective change than those without.

Reframing Resistance: From Obstacle to Intelligence

Here’s where many transformation efforts stumble: they treat resistance as a problem to eliminate rather than a signal to decode.

The traditional view positions resistance as obstruction – employees who don’t want to change, who are attached to the status quo, who need to be overcome or worked around. This framing creates an adversarial dynamic that actually increases resistance and reduces the quality of your final solution.

Emerging research takes a fundamentally different approach. When resistance is examined through a diagnostic lens, rather than a moral one, it frequently reveals legitimate concerns about change design, timing, or implementation strategy. Employees resisting a system implementation might not be resisting the system. They might be flagging that the proposed workflow doesn’t actually fit how work gets done, or that training timelines are unrealistic given current workload.

This distinction matters enormously. When you treat resistance as feedback, you create the psychological safety required for people to surface concerns early, when you can actually address them. When you treat it as defiance to be overcome, you drive concerns underground, where they manifest as passive non-adoption, workarounds, and sustained disengagement.

In one organisation undergoing significant operating model change, initial resistance from middle managers was substantial. Rather than pushing through, change leaders conducted structured interviews to understand the resistance. What they discovered: managers weren’t rejecting the new model conceptually. They were pointing out that the proposed changes would eliminate their ability to mentor direct reports – a core part of how they defined their role. This insight, treated as valuable feedback rather than insubordination, led to redesign of the operating model that preserved mentoring relationships whilst achieving transformation objectives. Adoption accelerated dramatically once this concern was addressed.

This doesn’t mean all resistance should be accommodated. In some cases, resistance does reflect genuine attachment to the past and reluctance to embrace necessary change. The discipline lies in differentiating between valid feedback and status quo bias.

How to operationalise this:

- Establish structured feedback channels specifically designed for change concerns. These shouldn’t be the normal communication cascade. Create forums, focus groups, anonymous feedback tools, skip-level conversations – where people can surface concerns about change design without fear of retaliation.

- Analyse resistance patterns for themes and root causes. When multiple people resist in similar ways, it’s rarely about personalities. Aggregate anonymous feedback, code for themes, and investigate systematically. Are concerns about training? Timing? Fairness? Feasibility? Resource constraints? Different root causes require different responses.

- Close the loop visibly. When someone raises a concern, respond to it, either by explaining why you’ve decided to proceed as planned, or by describing how feedback has shaped your approach. This signals that resistance was genuinely heard, even if not always accommodated.

- Use resistance reduction as a leading indicator of implementation quality. Research shows organisations applying appropriate resistance management techniques increase adoption by 72% and decrease employee turnover by almost 10%. This isn’t about eliminating resistance – it’s about responding to it in ways that increase trust and improve change quality.

Leading Transformation Exposes Your Leadership Gaps

Here’s what change initiatives reliably do: they force your existing leadership capability into sharp focus.

A director who’s excellent at managing steady-state operations often struggles when asked to lead across ambiguity and incomplete information. A manager skilled at optimising existing processes may lack the imaginative thinking required to design new ways of working. An executive effective at building consensus in stable environments might not have the decisiveness needed to make trade-off decisions under transformation pressure.

Transformation is unforgiving feedback. It exposes capability gaps faster and more visibly than traditional performance management ever could. The research is clear: organisations that succeed at transformation don’t pretend capability gaps don’t exist. They address them quickly and deliberately.

The default approach: Training programmes, capability workshops, external coaching, often fails because it assumes the gap is simply knowledge or skill. Sometimes it is. But frequently, capability gaps in transformation contexts reflect deeper factors: mindset constraints, emotional responses to change, discomfort with uncertainty, or different values about what leadership should look like.

Organisations achieving substantial transformation success take a markedly different approach. They conduct rapid capability assessments at the outset, identify the specific behaviours and mindsets required for transformation leadership, and then deploy layered interventions. These combine traditional training with experiential learning (assigning leaders to actually manage real change challenges, supported by coaching), peer learning networks where leaders grapple with similar issues, and visible role modelling by senior leaders who demonstrate the required behaviours consistently.

Critically, they also make hard personnel decisions. Some leaders simply cannot make the shift required. Rather than letting them continue in roles where they’ll block progress, high-performing organisations move them – sometimes into different roles within the organisation, sometimes out. This sends a powerful signal about how seriously transformation is being taken.

Making this operational:

- Conduct a leadership capability audit at transformation kickoff. Map the leadership capabilities you’ll need across your transformation – things like “comfort with ambiguity,” “ability to engage authentically,” “capacity for decisive decision-making,” “skills in difficult conversations,” “comfort with iterative approaches.” Then assess your current leadership against these requirements. Where are the gaps?

- Design layered development interventions targeting actual capability gaps, not generic leadership development. If your gap is discomfort with uncertainty, a workshop on change methodology won’t help. You need supported experience managing real ambiguity, plus coaching to help process the emotional content. If your gap is authentic engagement, you need to understand what’s preventing transparency, fear? Different values? Habit? And address the root cause.

- Use transformation experience as primary development currency. Research on leadership development shows that leaders develop most effectively through supported challenging assignments rather than classroom training. Assign high-potential leaders to lead specific transformation workstreams, with clear sponsorship, regular feedback, and peer learning opportunities. This builds capability whilst ensuring transformation gets skilled leadership.

- Make role model behaviour a deliberate leadership strategy. Senior leaders should visibly demonstrate the behaviours required for successful transformation. If you’re asking for greater transparency, senior leaders need to model transparency – including about uncertainties and setbacks. If you’re asking for iterative decision-making, senior leaders need to show themselves making decisions with incomplete information and adjusting based on feedback.

- Have uncomfortable conversations about fit. If someone in a critical leadership role consistently struggles with required transformation capabilities and shows limited willingness to develop, you need to address it. This doesn’t necessarily mean termination – it might mean moving to a different role where their strengths are better deployed, but it cannot be avoided if transformation is truly important.

Authentic Engagement: The Alternative to Corporate Speak

There’s a particular type of communication that emerges in most organisational transformations. Leaders craft carefully worded change narratives, develop consistent messaging, ensure everyone delivers the same talking points. The goal is alignment and consistency.

The problem is that people smell inauthenticity from across the room. When leaders are “spinning” change into positive language that doesn’t match lived experience, employees notice. Trust erodes. Cynicism increases. Adoption drops.

Research on authentic leadership in change contexts is striking: authentic leaders generate significantly higher organisational commitment, engagement, and openness to change. But authenticity isn’t about lowering guardrails or disclosing everything. It’s about honest communication that acknowledges complexity, uncertainty, and impact.

Compare two change communications:

Version 1 (inauthentic): “This transformation is an exciting opportunity that will energise our company and create amazing new possibilities for everyone. We’re confident this will be seamless and everyone will benefit.”

Version 2 (authentic): “This transformation is necessary because our current operating model won’t sustain us competitively. It will create new possibilities and some losses, for some roles and teams, the impact will be significant. I don’t fully know how it will unfold, and we’re likely to encounter obstacles I can’t predict. What I can promise is that we’ll make decisions as transparently as we can, we’ll listen to what you’re experiencing, and we’ll adjust our approach based on what we learn.”

Which builds trust? Which is more likely to generate genuine commitment rather than compliant buy-in?

Employees experiencing transformation are already managing significant ambiguity, loss, and stress. They don’t need corporate-speak that dismisses their experience. They need leaders willing to acknowledge what’s hard, be honest about uncertainties, and demonstrate genuine interest in their concerns.

Practising authentic engagement:

- Before you communicate, get clear on what you actually believe. Are you genuinely confident about aspects of this transformation, or are you performing confidence? Which parts feel uncertain to you personally? What concerns do you have? Authentic communication starts with honesty about your own experience.

- Acknowledge both benefits and costs. Don’t pretend that transformation will be wholly positive. Be specific about what people will gain and what they’ll lose. For some roles, responsibilities will expand in ways many will find energising. For others, familiar aspects of work will disappear. Both things are true.

- Create regular forums for two-way conversation, not just broadcasts. One-directional communication breeds cynicism. Create structured opportunities, skip-level conversations, focus groups, open forums, where people can ask genuine questions and get genuine answers. If you don’t know an answer, say so and commit to finding out.

- Acknowledge what you don’t know and what might change. Transformation rarely unfolds exactly as planned. The timeline will shift. Some approaches won’t work and will need redesign. Some impacts you predicted won’t materialise; others will surprise you. Saying this upfront sets realistic expectations and makes you more credible when things do need to change.

- Demonstrate consistency between your words and actions. If you’re asking people to embrace ambiguity but you’re communicating false certainty, the inconsistency speaks louder than your words. If you’re asking people to focus on customer impact but your decisions prioritise financial metrics, that inconsistency is visible. Authenticity is built through alignment between what you say and what you do.

Mapping Change: Creating Clarity Amidst Complexity

One of the most practical yet consistently neglected practices in transformation is a clear mapping of what’s changing, how it’s changing, and to what extent.

In organisations managing multiple changes simultaneously, this mapping is essential for a basic reason: people need to understand the shape of their changed experience. Will their team structure change? Will their workflow change? Will their career trajectory change? Will their reporting relationship change? Most transformation communications address these questions implicitly, if at all.

Research on change readiness assessments shows that clarity about scope, timing, and personal impact is one of the strongest predictors of readiness. Conversely, ambiguity about what’s changing drives anxiety, rumour, and resistance.

The best transformations make change mapping explicit and available. They’re clear about:

- What is changing (structure, processes, systems, roles, location, working arrangements)

- What is not changing (this is often as important as clarity about what is)

- How extent of change varies across the organisation (some roles will be substantially transformed; others minimally affected; some will experience change in specific dimensions but stability in others)

- Timeline of change (when different elements are scheduled to shift)

- Implications for specific groups (how a particular role, team, or function will experience the change)

This might sound straightforward, but in practice, most organisations communicate change narratives without this specificity. They describe the strategic intent without translating it into concrete impacts.

Creating effective change mapping:

- Start with a change impact matrix. Create a simple framework mapping roles/teams against change dimensions (structure, process, systems, location, reporting, scope of role, etc.). For each intersection, rate the extent of change: Significant, Moderate, Minimal, No change. This becomes the backbone of change communication.

- Translate this into role-specific change narratives. Take the matrix and develop specific descriptions for different role categories. A customer-facing role might experience process changes and system changes but minimal structural change. A support function might experience structural redesign but minimal customer-facing process impact. Be specific.

- Communicate extent and sequencing. Be clear about timing. Not everything changes immediately. Some changes are sequential; some are parallel. Some land in Phase 1; others in Phase 2. This clarity reduces anxiety because people can mentally organise the transformation rather than experiencing it as amorphous and unpredictable.

- Make space for questions about implications. Once people understand what’s changing, they’ll have questions about what it means for them. Create structured opportunities to explore these – guidance documents, Q&A sessions, role-specific workshops. The goal is to move from conceptual understanding to practical clarity.

- Update the mapping as change evolves. Your initial change map won’t be perfect. As implementation proceeds and you learn more, update it. Share updates with the organisation. This demonstrates that clarity is an ongoing commitment, not a one-time exercise.

Iterative Leadership: Why Linear Approaches Underperform

Traditional change methodologies are largely linear: plan, design, build, test, launch, embed. Each phase has defined gates and decision points. This approach works well for changes with clear definition, stable requirements, and predictable implementation.

But transformation, by definition, involves substantial ambiguity. You’re asking your organisation to operate differently, often in ways that haven’t been fully specified upfront. Linear approaches to highly ambiguous change create friction: they generate extensive planning documentation to address uncertainties that can’t be fully resolved until you’re actually in implementation, they create fixed timelines that often become unrealistic once you encounter real-world complexity, and they limit your ability to adjust course based on what you learn.

The research is striking on this point. Organisations using iterative, feedback-driven change approaches achieve 6.5 times higher success rates than those using linear approaches. The mechanisms are clear: iterative approaches enable real-time course correction based on implementation learning, they surface issues early when they’re easier to address, and they build confidence through early wins rather than betting everything on a big go-live moment.

Iterative change leadership means several specific things:

Working in short cycles with clear feedback loops. Rather than designing everything upfront, you design enough to move forward, implement, gather feedback, learn, and adjust. This might mean launching a pilot with a subset of users, gathering feedback intensively, redesigning based on learning, and then rolling forward. Each cycle is 4-8 weeks, not 12-18 months.

Building in reflection and adaptation as deliberate process. After each cycle, create space to debrief: What did we learn? What worked? What needs to be different? What surprised us? Use this learning to shape the next cycle. This is fundamentally different from having a fixed plan and simply executing it.

Treating resistance and issues as valuable navigation signals. When something doesn’t work in an iterative approach, it’s not a failure, it’s data. What’s not working? Why? What does this tell us about our assumptions? This learning shapes the next iteration.

Empowering local adaptation within a clear strategic frame. You set the strategic intent clearly – here’s what we’re trying to achieve – but you allow significant flexibility in how different parts of the organisation get there. This is the opposite of “rollout consistency,” but it’s far more effective because it allows you to account for local context and differences in readiness.

Practically, this looks like:

- Move away from detailed future-state designs. Instead, define clear strategic intent and outcomes. Describe the principles guiding change. Then allow implementation to unfold more flexibly.

- Work in 4-8 week cycles with explicit feedback points. Don’t try to sustain a project for 18 months without meaningful checkpoints. Create structured points where you pause, assess what’s working and what isn’t, and decide what to do next.

- Create cross-functional teams that stay together across cycles. This creates continuity of learning. These teams develop intimate understanding of what’s working and where issues lie. They become navigators rather than order-takers.

- Establish feedback mechanisms specifically designed to surface early issues. Don’t rely on adoption data that only appears 3 months post-launch. Create weekly or bi-weekly pulse checks on specific dimensions: Is training working? Are systems stable? Are processes as designed actually workable? Are people finding new role clarity?

- Build adaptation explicitly into governance. Rather than fixed steering committees that monitor against plan, create governance that actively discusses early signals and makes real decisions about adaptation.

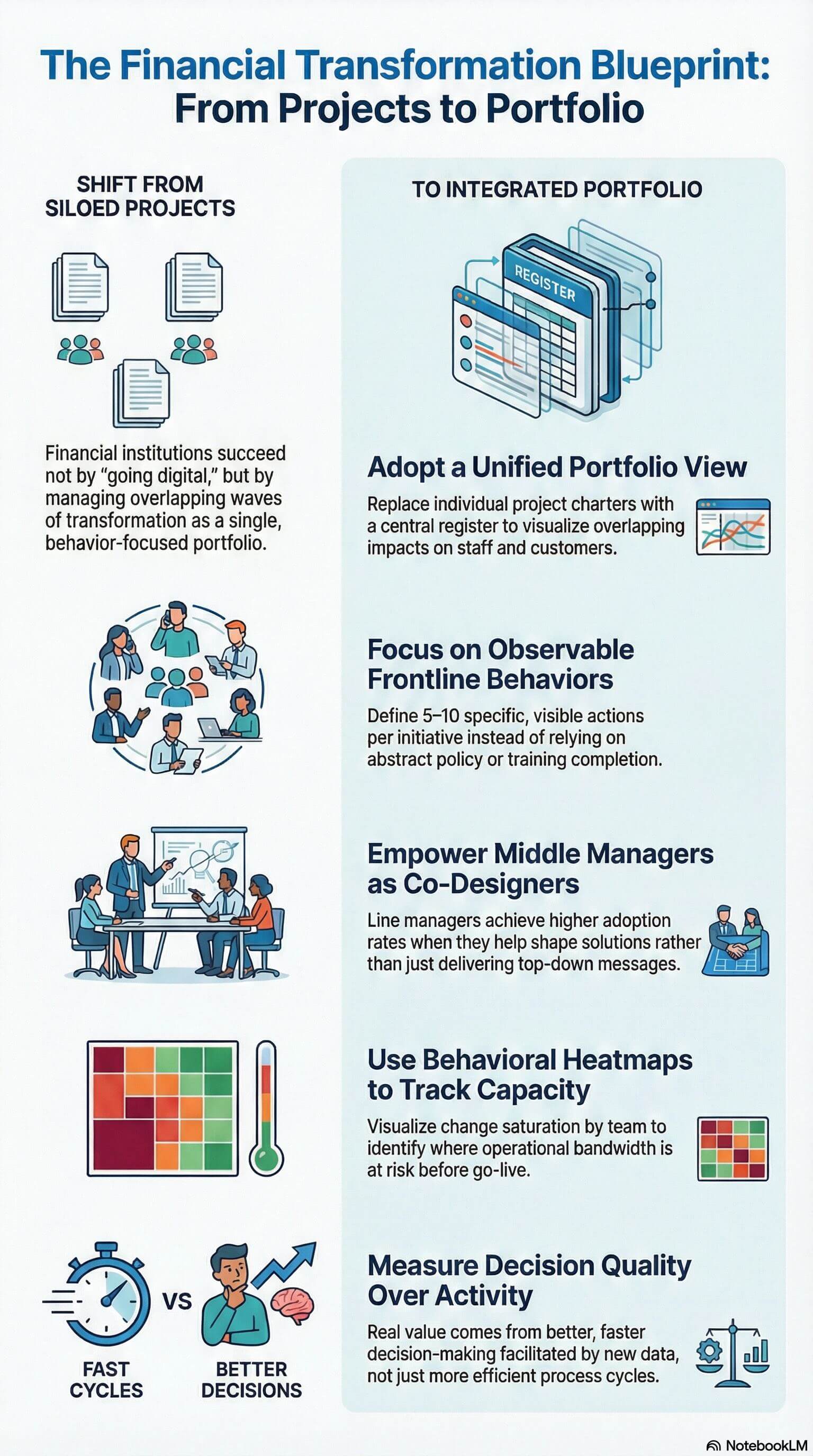

Change Portfolio Perspective: The Essential Systems View

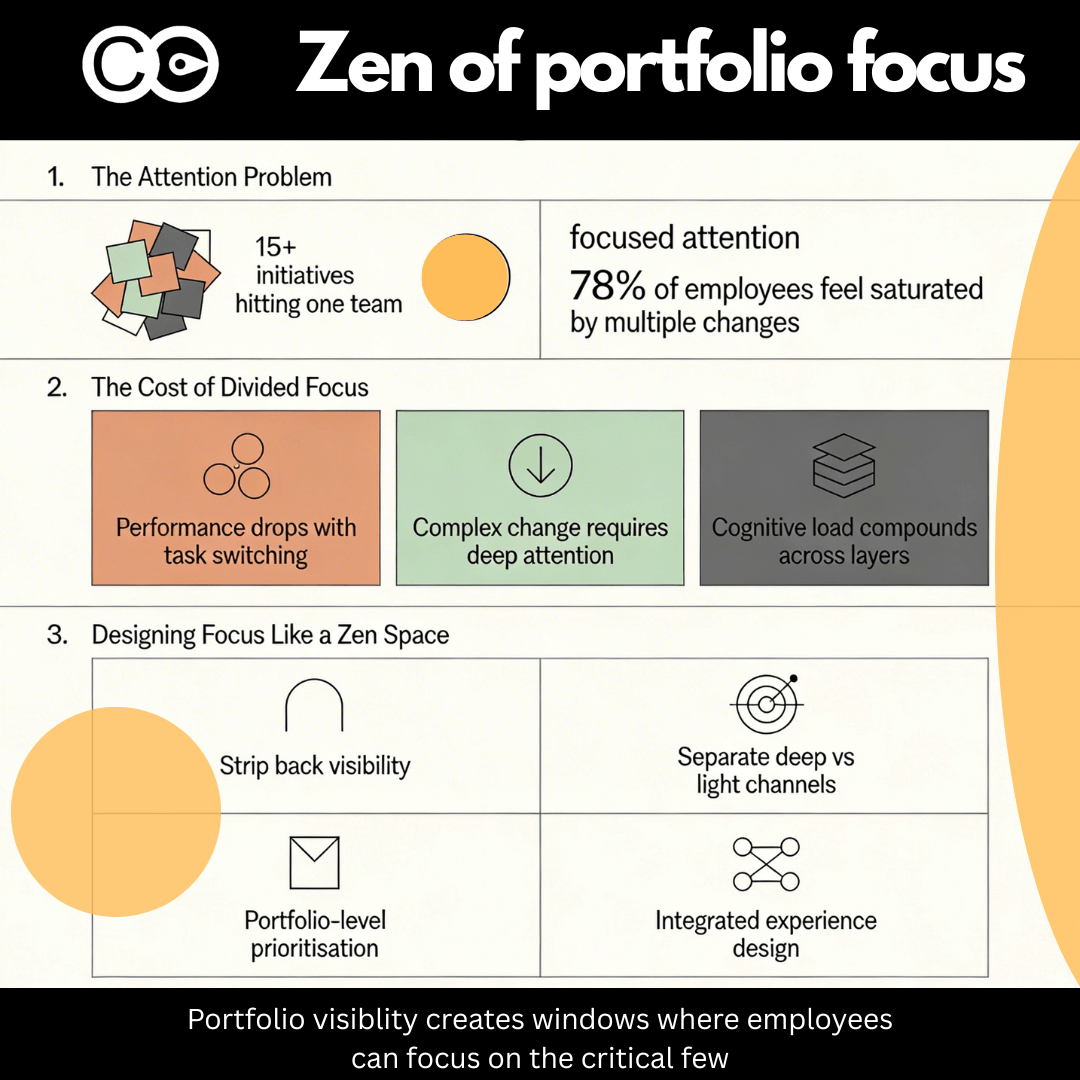

Most transformation efforts pay lip service to change portfolio management but approach it as an administrative exercise. They track which initiatives are underway, their status, their resourcing. But they don’t grapple with the most important question: What is the aggregate impact of all these changes on our people and our ability to execute business-as-usual?

This is where change saturation becomes a critical business risk.

Research on organisations managing multiple concurrent changes reveals a sobering pattern: 78% of employees report feeling saturated by change. More concerning: when saturation thresholds are crossed, productivity experiences sharp declines. People struggle to maintain focus across competing priorities. Change fatigue manifests in measurable outcomes: 54% of change-fatigued employees actively look for new roles, compared to just 26% experiencing low fatigue.

The research demonstrates that capacity constraints are not personality issues or individual limitations – they reflect organisational capacity dynamics. When the volume and intensity of change exceeds organisational capacity, even high-quality individual leadership can’t overcome systemic constraints.

This means treating change as a portfolio question, not a collection of individual initiatives, becomes non-negotiable in transformation contexts.

Operationalising portfolio perspective:

- Create a change inventory that captures the complete change landscape. This means including not just major transformation initiatives, but BAU improvement projects, system implementations, restructures, and process changes. Ask teams: What changes are you managing? Map these comprehensively. Most organisations discover they’re asking people to absorb far more change than they realised.

- Assess change impact holistically across the organisation. Using the change inventory, create a heat map showing change impact by team or role. Are certain teams carrying disproportionate change load? Are some roles involved in 5+ concurrent initiatives while others are relatively unaffected? This visibility itself drives change.

- Make deliberate trade-off decisions based on capacity. Rather than asking “Can we do all of these initiatives?” ask “If we do all of these, what’s the realistic probability of success and what’s the cost to business-as-usual?” Sometimes the answer is “We need to defer initiatives.” Sometimes it’s “We need to sequence differently.” But these decisions should be explicit, made by leadership with clear line of sight to change impact.

- Use saturation assessment as part of initiative governance. Before approving a new initiative, require assessment: How does this fit in our overall change portfolio? What’s the cumulative impact if we do this along with what’s already planned? Is that load sustainable?

- Create buffers and white space deliberately. Some of the most effective organisations build “change free” periods into their calendar. Not everything changes simultaneously. Some quarters are lighter on new change initiation to allow embedding of recent changes.

The Change Compass Approach: Technology Enabling Better Change Leadership

As organisations scale their transformation capability, the manual systems that worked for single initiatives or small portfolios break down. Spreadsheets don’t provide real-time visibility. Email-based feedback isn’t systematic. Adoption tracking conducted through surveys happens too infrequently to be actionable.

This is where structured change management technology like The Change Compass becomes valuable. Rather than replacing leadership judgment, effective digital tools enable better leadership by:

- Providing real-time visibility into change metrics. Rather than waiting for monthly reports, leaders have weekly visibility into adoption rates, readiness scores, engagement levels, and emerging issues across their change portfolio.

- Systematising feedback collection and analysis. Tools like pulse surveys can be deployed continuously, allowing you to track sentiment, identify emerging concerns, and respond in real time rather than discovering problems months after they’ve taken root.

- Aggregating change data across the portfolio. You can see not just how individual initiatives are performing, but how aggregate change load is affecting specific teams, roles, or functions.

- Democratising data visibility across leadership layers. Rather than keeping change metrics confined to change professionals, you can make data accessible to line leaders, executives, and business leaders, helping them understand change dynamics and take appropriate action.

- Supporting hypothesis-driven decision-making. Rather than collecting data and hoping it’s relevant, tools enable you to design specific data collection around hypotheses you’re testing.

The critical point is that technology is enabling, not substituting. The human leadership decisions—about change strategy, pace, approach, resource allocation, and adaptation—remain with leaders. But they can make these decisions with better information and clearer visibility.

Bringing It Together: The Practical Next Steps

The practices described above aren’t marginal improvements to how you currently approach transformation. They represent a fundamental shift from traditional change management toward strategic change leadership.

Here’s how to begin moving in this direction:

Phase 1: Assess current state (4 weeks)

- Map your current change portfolio. What’s actually underway?

- Assess leadership capability against transformation requirements. Where are the gaps?

- Evaluate your current measurement approach. What are you actually seeing?

- Understand your change saturation levels. How much change are people managing?

Phase 2: Design transformation leadership model (4-6 weeks)

- Define the leadership behaviours and capabilities required for your specific transformation.

- Identify your measurement framework—what will you measure, how frequently, through what mechanisms?

- Clarify your iterative approach—how will you work in cycles rather than linear phases?

- Design your engagement strategy—how will you create authentic dialogue around change?

Phase 3: Implement with intensity (ongoing)

- Address identified leadership capability gaps deliberately and immediately.

- Launch your feedback mechanisms and establish regular cadence of learning and adaptation.

- Begin your first change cycle with deliberate reflection and adaptation built in.

- Share change mapping and clear impact communication with your organisation.

The organisations that succeed at transformation – that emerge with sustained new capability rather than exhausted people and stalled initiatives – do so because they treat change leadership as a strategic competency, not an administrative function. They build their approach on evidence about what actually works, they create structures for honest dialogue about what’s hard, and they remain relentlessly focused on whether their organisation actually has capacity for what they’re asking of it.

That clarity, grounded in data and lived experience, is what separates transformation that transforms from change initiatives that create fatigue without progress.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What are the research-proven best practices for leading organisational transformation?

Research-backed practices include using continuous data for decision-making rather than intuition alone, treating resistance as diagnostic feedback, developing transformation-specific leadership capabilities, communicating authentically about impacts and uncertainties, mapping change impacts explicitly for different groups, and managing change as an integrated portfolio to avoid saturation. These principles emerge consistently from studies of transformational leadership, change readiness and implementation effectiveness.

How does data-driven change leadership differ from relying on conversations?

Data-driven leadership uses structured metrics on adoption, readiness and capacity to identify issues at scale, while conversations provide qualitative context and verification. Studies show organisations with continuous feedback loops achieve 25-35% higher adoption rates and are 6.5 times more likely to succeed than those depending primarily on informal discussions. The combination works best for complex transformations.

Should resistance to change be treated as feedback or an obstacle?

Resistance often signals legitimate concerns about design, timing, fairness or capacity, functioning as valuable diagnostic information when analysed systematically. Research recommends structured feedback channels to distinguish adaptive resistance (design issues) from non-adaptive attachment to the status quo, enabling targeted responses that improve outcomes rather than adversarial overcoming.

How can leaders engage authentically during transformation?

Authentic engagement involves honest communication about benefits, costs, uncertainties and decision criteria, avoiding overly polished messaging that erodes trust. Empirical studies link authentic and transformational leadership behaviours to higher commitment and lower resistance through perceived fairness and consistency between words and actions. Leaders should acknowledge trade-offs explicitly and invite genuine questions.

What leadership capabilities are most critical for transformation success?

Research identifies articulating a credible case for change, involving others in solutions, showing individual consideration, maintaining consistency under ambiguity, and modelling required behaviours as key. Capability gaps in these areas become visible during transformation and require rapid assessment, targeted development through challenging assignments, and sometimes personnel decisions.

How do organisations avoid change saturation across multiple initiatives?

Effective organisations maintain an integrated portfolio view, map cumulative impact by team and role, assess capacity constraints regularly, and make explicit trade-offs about sequencing, delaying or stopping initiatives. Studies show change saturation drives fatigue, turnover intentions and performance drops, with 78% of employees reporting overload when managing concurrent changes.

Why is mapping specific change impacts important?

Clarity about what will change (and what will not), for whom, and when reduces uncertainty and improves readiness. Research on change readiness finds explicit impact mapping predicts higher constructive engagement and smoother adoption, while ambiguity about personal implications increases anxiety and resistance.

Can generic leadership development prepare leaders for transformation?

Generic training shows limited impact. Studies emphasise development through supported challenging assignments, real-time feedback, peer learning and coaching targeted at transformation-specific behaviours like navigating ambiguity and authentic engagement. Leader identity and willingness to own change outcomes predict effectiveness more than formal programmes.

What role does organisational context play in transformation success?

Meta-analyses confirm no single “best practice” applies universally. Outcomes depend on culture, change maturity, leadership capability and pace. Effective organisations adapt evidence-based principles to their context using internal data on capacity, readiness and leadership behaviours.

How can transformation leaders measure progress effectively?

Combine continuous quantitative metrics (adoption rates, readiness scores, capacity utilisation) with qualitative feedback analysis. Research shows this integrated approach enables early issue detection and course correction, significantly outperforming periodic or anecdotal assessment. Focus measurement on leading indicators of future success alongside lagging outcome confirmation.