Agile has become the technical operating model for large organisations. You’ll find Scrum teams in finance, Kanban boards in HR, Scaled Agile frameworks spanning entire technology divisions. The velocity and responsiveness are real. What’s also becoming real, though less often discussed, is the hidden cost: when agile technical delivery isn’t matched with agile change management, employees experience whiplash rather than transformation.

A financial services firm we worked with exemplifies the problem. They had implemented SAFe (Scaled Agile) across 150 people split into 12 Agile Release Trains (ARTs). Each ART could ship features in 2-week sprints. The technical execution was solid. But frontline teams found themselves managing changes from five different initiatives simultaneously. Loan officers had training sessions every two weeks. Operations teams were learning new systems before they’d embedded the previous one. The organisation was delivering change at maximum velocity into people who had hit their saturation limit months earlier. After three quarters, they’d achieved technical agility but created change fatigue that actually slowed adoption and spiked operations disruption.

This scenario repeats across industries because organisations may have solved the technical orchestration problem without solving the human orchestration problem. Scaled Agile frameworks like SAFe address how distributed technical teams coordinate delivery. They’re silent on how those technical changes orchestrate employee experience across the organisation. That silence is the gap this article addresses.

The agile norm and the coordination challenge it creates

Agile as a delivery model is now standard practice. What’s still emerging is how organisations manage the change that agile delivery creates at scale.

Here’s the distinction. When a single agile team builds a feature, the team manages its own change: they decide on testing approach, communication cadence, stakeholder engagement. When 12 ARTs build different capabilities simultaneously – a new customer data platform, a revised underwriting workflow, a redesigned payments system – the change impacts collide. Different teams create different messaging. Training runs parallel rather than sequenced. Employee readiness and adoption are fragmented across initiatives.

The heart of the problem is this: agile teams are optimised for one thing, delivering customer-facing capability quickly and iteratively. They operate with sprint goals, velocity metrics, and deployment cadences measured in days. Change – the human, business, and operational impacts of what’s being delivered – operates on different cycles. Change readiness takes weeks or months. Adoption roots over months. People can internalise 2-3 concurrent changes effectively; beyond that, fatigue or inadequate attention set in and adoption rates fall.

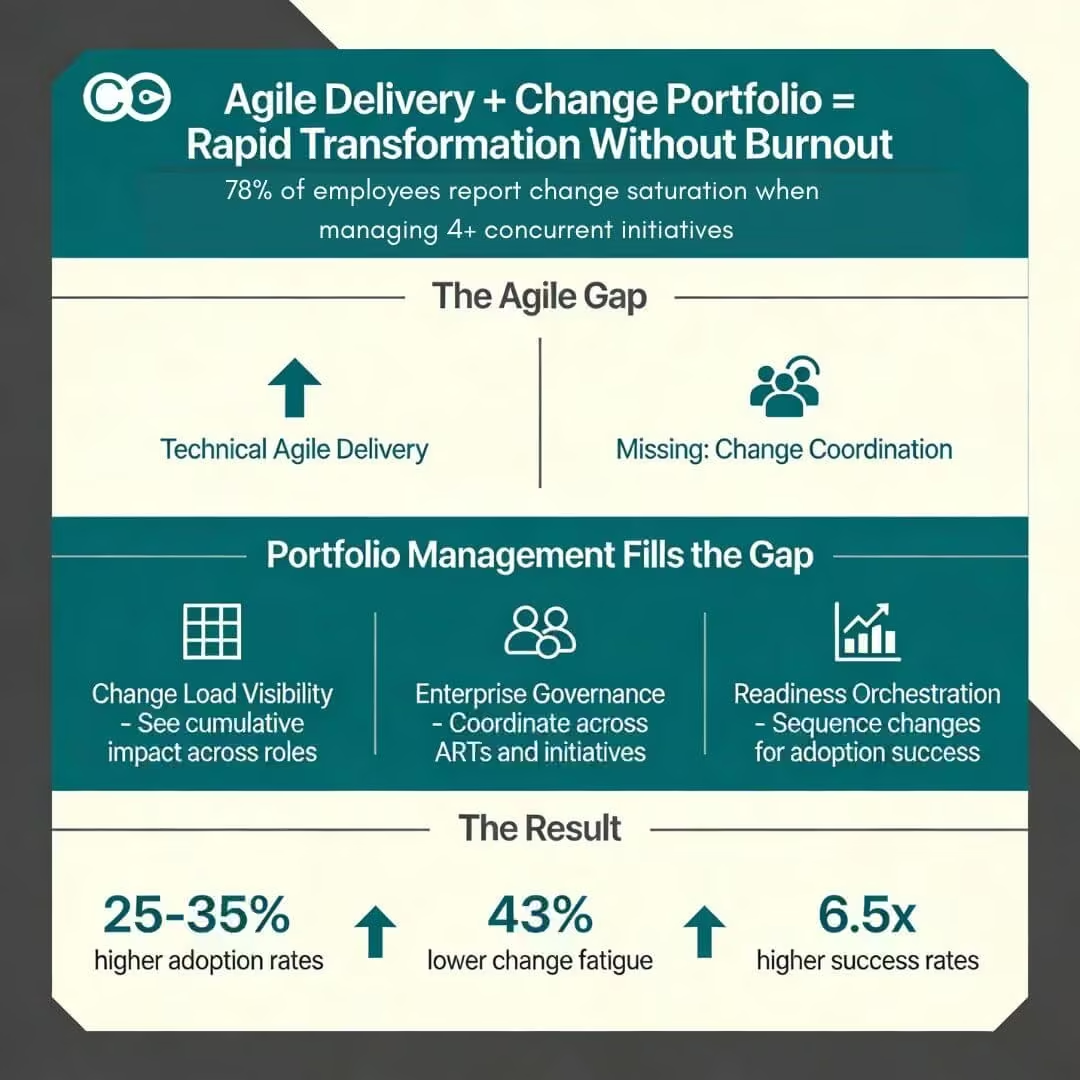

Research into agile transformations confirms this tension: 78% of employees report feeling saturated by change when managing concurrent initiatives, and organisations where saturation thresholds are exceeded experience measurable productivity declines and turnover acceleration. Yet these same organisations have achieved technical agile excellence.

The solution isn’t to slow agile delivery. It’s to apply agile principles to change itself – specifically, to orchestrate how multiple change initiatives coordinate their impacts on people and the organisation.

What standard agile practices deliver and where they fall short

Standard agile practices are designed around one core principle: break complex work into smaller discrete pieces, iterate fast in smaller cycles, and use small cross-functional teams to deliver customer outcomes efficiently.

Applied to technical delivery, this works remarkably well. Breaking a major system redesign into two-week sprints means you get feedback every fortnight. You can course-correct within days rather than discovering fatal flaws after six months of waterfall planning. Smaller teams move faster and communicate better than large programmes. Cross-functional teams reduce handoffs and accelerate decision-making.

The effectiveness is measurable. Organisations using iterative, feedback-driven approaches achieve 6.5 times higher success rates than those using linear project management. Continuous measurement delivers 25-35% higher adoption rates than single-point assessments.

But here’s where most organisations get stuck: they implement these technical agile practices without designing the connective glue across initiatives.

Agile thinking within a team doesn’t automatically create agile orchestration across teams. The coordination mechanisms required are different:

Within a team: Agile ceremonies (daily standups, sprint planning, retrospectives) keep a small group aligned. The team shares context daily and adjusts course together.

Across an enterprise with 12 ARTs: There’s no daily standup where everyone appears. There’s no single sprint goal. Different ARTs deploy on different cadences. Without explicit coordination structures, each team optimises locally – which means each team’s change impacts ripple outward without visibility into what other teams are doing.

A customer service rep experiences this fragmentation. Monday she’s in training for the new loan decision system (ART 1). Wednesday she learns the updated customer data workflow (ART 2). Friday she’s reoriented on the new phone system interface (ART 3). Each change is well-designed. Each training is clear. But the content and positioning of these may not be aligned, and their cumulative impact overwhelms the rep’s capacity to learn and embed new ways of working.

The gap isn’t in the quality of individual agile teams. The gap is in the orchestration infrastructure that says: “These three initiatives are landing simultaneously for this population. Let’s redesign sequencing or consolidate training or defer one initiative to create breathing room.” That kind of orchestration requires visibility and decision-making above the individual ART level.

The missing piece: Enterprise-level change coordination

A lot of large organisations have some aspects of scaled agile approach. SAFe includes Program Increment (PI) Planning – a quarterly event where 100+ people from multiple ARTs align on features, dependencies, and capacity across teams. PI Planning is genuinely useful for technical coordination. It prevents duplicate work. It surfaces dependency chains. It creates realistic capacity expectations.

But PI Planning is built for technical delivery, not change impact. It answers: “What will we build this quarter?” It doesn’t answer: “What change will people experience? Which teams face the most disruption? What’s the cumulative employee impact if we proceed as planned?”

This is where change portfolio management enters the picture.

Change portfolio management takes the same orchestration principle that PI Planning applies to features – explicit, cross-team coordination – and applies it to the human and business impacts of change. It answers questions PI Planning can’t:

- How many concurrent changes is each role absorbing?

- When do we have natural low-change periods where we can embed recent changes before launching new ones?

- What’s the cumulative training demand if we proceed with current sequencing?

- Are certain teams becoming change-saturated whilst others have capacity?

- Which changes are creating the highest resistance, and what does that tell us about design or readiness?

Portfolio management provides three critical functions that distributed agile teams don’t naturally create:

1. Employee/customer change experience design

This means deliberately designing the end-to-end experience of change from the employee’s perspective, not the project’s perspective. If a customer service rep is affected by five initiatives, what’s the optimal way to sequence training? How do we consolidate messaging across initiatives? How do we create clarity about what’s changing vs. what’s staying the same?

Rather than asking “How does each project communicate its changes?”—which creates five separate messaging streams—portfolio management asks “How does the organisation communicate these five changes cohesively?” The difference is profound. It shifts from coordination to integration.

2. People impact monitoring and reporting

Portfolio management tracks metrics that individual projects miss:

- Change saturation per role type: Is the finance team absorbing 2 changes or 7?

- Readiness progression: Are training completion rates healthy across initiatives or are they clustering in some areas?

- Adoption trajectories: Post-launch, are people actually using new systems/processes or finding workarounds?

- Fatigue indicators: Are turnover intentions rising in heavily impacted populations?

These metrics don’t appear in project dashboards because they’re enterprise metrics and not about project delivery. Individual projects see their own adoption. The portfolio sees whether adoption is hindered by saturation in an adjacent initiative.

3. Readiness and adoption design at organisational level

Rather than each project running its own readiness assessment and training programme, portfolio management creates:

- A shared readiness framework applied consistently across initiatives, allowing apple-to-apple comparisons

- Sequenced capability building (you embed the customer data system before launching the new workflow that depends on clean data)

- Consolidated training calendars (rather than five separate training schedules)

- Shared adoption monitoring (one dashboard showing whether organisations are actually using the changes or resisting them)

The orchestration infrastructure required

Supporting rapid transformation without burnout requires four specific systems:

1. Change governance across business and enterprise levels

Governance isn’t bureaucracy here. It’s decision-making structure. You need forums where:

Initiative-level change governance (exists in most organisations):

- Project sponsor, change lead, communications lead meet weekly

- Decisions: messaging, training content, resistance management, adoption tactics

- Focus: making this project’s change land successfully

Enterprise-level change governance (often missing):

- Representatives from each ART, plus HR, plus finance, plus communications

- Meet biweekly

- Decisions: sequencing of initiatives, portfolio saturation, resource allocation across change efforts, blackout periods

- Focus: managing cumulative impact and capacity across all initiatives

The enterprise governance layer is where PI Planning concepts get applied to people. Just as technical PI Planning prevents two ARTs from building the same feature, enterprise change governance prevents two initiatives from saturating the same population simultaneously.

2. Load monitoring and reporting

You can’t manage what you don’t measure. Portfolio change requires visibility into:

Change unit allocation per role

Create a simple matrix: Across the vertical axis, list all role types/teams. Across the horizontal axis, list all active initiatives (not just IT – include process changes, restructures, system migrations, anything requiring people to work differently). For each intersection, mark which initiatives touch which roles.

The heatmap becomes immediately actionable. If Customer Service is managing 4 decent-sized changes simultaneously, that’s saturation territory. If you’re planning to launch Programme 5, you know it cannot hit Customer Service until one of their current initiatives is embedded.

Saturation scoring

Develop a simple framework:

- 1-2 concurrent changes per role = Green (sustainable)

- 3 concurrent changes = Amber (monitor closely, ensure strong support)

- 4+ concurrent changes = Red (saturation, adoption at risk)

Track this monthly. When saturation appears, trigger decisions: defer an initiative, accelerate embedding of a completed initiative, add change support resources.

When you’re starting out this is the first step. However, when you’re managing a large enterprise with a large volume of projects as well as business-as-usual initiatives, you need finer details in rating the level of impact at an initiative and impact activity level.

Training demand consolidation

Rather than five initiatives each scheduling 2-day training courses, portfolio planning consolidates:

- Weeks 1-3: Data quality training (prerequisite for multiple initiatives)

- Weeks 4-5: New systems training (customer data + general ledger)

- Week 6: Process redesign workshop

- Weeks 7-8: Embedding (no new training, focus on bedding in changes)

This isn’t sequential delivery (which would slow things down). It’s intelligent batching of learning so that people absorb multiple changes within a supportable timeframe rather than fragmenting across five separate schedules.

3. Shared understanding of heavy workload and blackout periods

Different parts of organisations experience different natural rhythms. Financial services has heavy change periods around year-end close. Retail has saturation during holiday season preparation. Healthcare has patient impact considerations that create unavoidable busy periods.

Portfolio management makes these visible explicitly:

Peak change load periods (identified 12 months ahead):

- January: Post-holidays, people are fresh, capacity exists

- March-April: Reporting season hits finance; new product launches hit customer-facing teams

- June-July: Planning seasons reduce availability for major training

- September-October: Budget cycles demand focus in multiple teams

- November-December: Year-end pressures spike across organisation

Then when sponsors propose new initiatives, the portfolio team can say: “We can launch this in January when capacity exists. If you push for launch in March, it collides with reporting season and year-end planning—adoption will suffer.” This creates intelligent trade-offs rather than first-come-first-served initiative approval.

Blackout periods (established annually):

Organisations might define:

- June-July: No major new change initiation (planning cycles)

- Week 1-2 January: No training or go-lives (people returning from holidays)

- Week 1 December: No launches (focus shifting to year-end)

These aren’t arbitrary. They reflect when the organisation’s capacity for absorbing change genuinely exists or doesn’t.

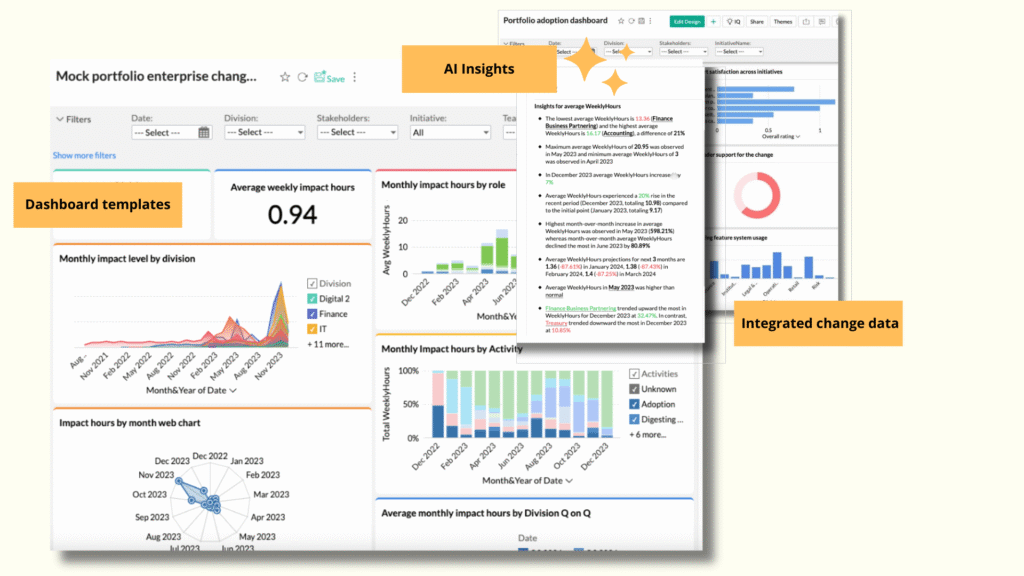

4. Change portfolio tools that enable this infrastructure

Spreadsheets and email can’t manage enterprise change orchestration at scale. You need tools that:

The Change Compass and similar platforms provide:

- Automated analytics generation: Each initiative updates its impacted roles. The tool instantly shows cumulative load by role.

- Saturation alerts: When a population hits red saturation, alerts trigger for governance review.

- Portfolio dashboard: Executives see at a glance which initiatives are proceeding, their status, and cumulative impact.

- Readiness pulse integration: Monthly surveys track training completion, system adoption, and readiness across all initiatives simultaneously.

- Adoption tracking: Post-launch data shows whether people are actually using new processes or finding workarounds.

- Reporting and analytics: Portfolio leads can identify patterns (e.g., adoption rates are lower when initiatives launch with less than 2 weeks between training completion and go-live).

Tools like this aren’t luxury add-ons. They’re infrastructure. Without them, enterprise governance becomes opinionated conversations and unreliable. With them, you have actionable data. The value is usually at least in the millions annually in business value.

Bringing this together: Implementation roadmap

Month 1: Establish visibility

- List all current and planned initiatives (next 12 months)

- Create role type-level impact matrix

- Generate first saturation heatmap

- Brief executive team on portfolio composition

Month 2: Establish governance

- Launch biweekly Change Coordination Council

- Define enterprise change governance charter

- Establish blackout periods for coming 12 months

- Train initiative leads on portfolio reporting requirements

Month 3-4: Design consolidated change experience

- Coordinate messaging across initiatives

- Consolidate training calendar

- Create shared readiness framework

- Launch portfolio-level adoption dashboard

Month 5+: Operate at portfolio level

- Biweekly governance meetings with real decisions about pace and sequencing

- Monthly heatmap review and saturation management

- Quarterly adoption analysis and course correction

- Initiative leads report against portfolio metrics, not just project metrics

The evidence for this approach

Organisations implementing portfolio-level change management see material differences:

- 25-35% higher adoption rates through coordinated readiness and reduced saturation

- 43% lower change fatigue scores in employee surveys

- 6.5x higher initiative success rates through iterative, feedback-driven course correction

- Retention improvement: Organisations with low saturation see voluntary turnover 31 percentage points lower than high-saturation peer companies

These aren’t marginal gains. This is the difference between transformation that transforms and change that creates fatigue.

The research is clear: iterative approaches with continuous feedback loops and portfolio-level coordination outperform traditional programme management. Agile delivery frameworks have solved technical orchestration. Portfolio management solves human orchestration. Together, they create rapid transformation without burnout.

For more insight on how to embed this approach within scaled frameworks, see Measure and Grow Change Effectiveness Within Scaled Agile.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why can’t PI Planning handle change coordination?

PI Planning coordinates technical features and dependencies. It doesn’t track people impact, readiness, or saturation across initiatives. Those require separate data collection and governance layers specific to change.

How is portfolio change management different from standard programme management?

Traditional programmes manage one large initiative. Change portfolio management coordinates impacts across multiple concurrent initiatives, making visible the aggregate burden on people and organisation.

Don’t agile teams already coordinate through standups and retrospectives?

Team-level coordination happens within an ART (agile release train). Enterprise coordination requires governance above team level, visible saturation metrics, and explicit trade-off decisions about which initiatives proceed and when. Without this, local optimisation creates global problems.

What size organisation needs portfolio change management?

Any organisation running 3+ concurrent initiatives needs some form of portfolio coordination. A 50-person firm might use a spreadsheet. A 500-person firm needs structured tools and governance.

How do we get Agile Release Train leads to participate in enterprise change governance?

Show the saturation data. When ART leads see that their initiative is stacking 4 changes onto a customer service team already managing 3 others, the case for coordination becomes obvious. Make governance meetings count—actual decisions, not information sharing.

Does portfolio management slow down agile delivery?

It resequences delivery rather than slowing it. Instead of five initiatives launching in week 5 (creating saturation), portfolio management might sequence them across weeks 3, 5, 7, 9, 11. Total delivery time is similar; adoption rates and employee experience improve dramatically.

What metrics should a portfolio dashboard show?

- Change unit allocation per role (saturation heatmap)

- Training completion rates across initiatives

- Adoption rates post-launch

- Employee change fatigue scores (pulse survey)

- Initiative status and timeline

- Readiness progression

How often should portfolio governance meet?

Monthly is standard. This allows timely response to emerging saturation without creating meeting overhead. Real governance means decisions get made—sequencing changes, reallocating resources, adjusting timelines.